/

May 23, 2022

/

#

Min Read

Cybersecurity and Data Protection Regulations in LATAM

Despite a significant dip in sales during the pandemic, the Latin American (LATAM) automotive market has a five-year projected CAGR of 4.61% to reach a valuation of 161.74 billion USD by 2027. Twenty-one countries and territories comprise LATAM and unlike Europe, where many governments fall under the jurisdiction of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), there is no single governing body that issues regulatory standards and oversees compliance.

This creates an interesting challenge for automotive OEMs. As the technological complexity and software dependency of connected vehicles increases, those wishing to continue business in LATAM will need to understand its myriad of data protection and cybersecurity regulations. What are these laws? How are they changing? And what do automakers need to do to prepare? Read on to find out.

The State of LATAM Cybersecurity Regulations and Data Protection Policies

Until a couple of decades ago, there was little need for cybersecurity regulations or data protection laws in LATAM. Aside from “big business” many companies functioned via personal interactions and low to non-existent levels of technological dependence. However, decarbonization of public transportation, improvements to transportation networks, goods distribution, and public utilities, along with a global pandemic, have created a significant shift in the LATAM business model.

This transition has opened the door to malicious cyberattacks and data breaches, leaving many countries scrambling to mitigate the issue. As such, many LATAM regulations are either in the works, vague, or still up for debate.

Brazil

The state of cybersecurity in Brazil became a hot topic after the country hosted several prestigious events including the World Cup and the Olympics. Concerned for their own protection, participating countries encouraged Brazil to improve its cybersecurity identification and response procedures.

The main body responsible for coordinating information security efforts is the Institutional Security Office of the Presidency (GSI). In conjunction with a presidential mandate, GSI helped create and define the National Information Security Policy. This policy suggests the development of five national strategies: cybersecurity, cyber defense, critical infrastructure protection, classified information security, and data leak protection.

The first of these, The National Cybersecurity Strategy (E-Ciber), aims to mitigate cyberattacks, improve threat resilience, and strengthen Brazil’s role in international cybersecurity through education, training, and awareness. One issue with E-Ciber is it is not actually a law. E-Ciber is a roadmap that offers “suggestions” and “recommendations” rather than strict guidelines, procedures, and consequences.

Brazil does, however, have clear data protection standards. The Brazilian General Data Protection Act (LGPD) came into effect in September 2020. It is Brazil’s first all-encompassing data protection regulation and applies to any data processing operation so long as:

- It is handled in Brazil

- Its purpose is to provide goods or services

- The data was collected in or pertains to individuals located in Brazil

These rules apply regardless of data processing means or the location of the data and its processor. It does not, however, apply when data is processed for non-financial or artistic purposes, for public safety, national security, defense, criminal prosecution, or if the data is shared or housed in a country that offers a comparable level of data protection as outlined by LGPD.

Mexico

Although Mexico does not have any regulations specific to cybersecurity, it has one of the most comprehensive data protection frameworks in LATAM. As of 2009, the protection of personal data became recognized as a Constitutional right. The Ley Federal de Protección de Datos Personales en Posesión de Particulares (LFPDPPP) outlines definitions and mandatory procedures while establishing INAI as the primary data protection authority.

Procedures include obtaining explicit consent from the data subject for collection, use, transfer, and storage, as well as maintaining records of consent. In addition, data controllers must implement physical, technical, and administrative security measures to protect data from damage, alteration, destruction, or unauthorized use. These measures must account for risks associated with potential security breaches and a response plan that includes data subject notification and advisement.

LFPDPPP also includes specific obligations for data processors. Processors must:

- Implement data protection security measures

- Process data per the controller’s instructions

- Process data for permitted purposes only

- Maintain confidentiality of processed data

- Delete data per the controller’s request

- Delete data when the controller/processor relationship is terminated

- Transfer data only when specified by the controller or required by law

As a final safeguard, a data protection authority or department must be appointed to ensure personal data protection and best practices in accordance with laws, regulations, and guidelines. Mexico is one of the only LATAM countries to define the scope of a “data breach,” leaving no room for misinterpretation of unacceptable and acceptable data usage.

Argentina

Although cybercrime is on Argentina's radar, little has been done to regulate it. In 2008 the country adopted the Cybercrime Law 26.388 which criminalized several forms of cybercrime. The law, however, is not comprehensive and does not include procedural requirements or best practices to ensure cybersecurity. Neither is there a designated body to oversee compliance.

In 2017 Argentina joined the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime, also known as the Budapest Convention, which works towards the international harmonization of cyber law. Members of the convention agree to criminalize certain activities and give their criminal justice system the power to investigate those crimes. Unfortunately, making something illegal and having regulations and enforcement in place to prevent it are two entirely different things.

Like Brazil and Mexico, Argentina emphasizes the importance of data protection, with its Personal Data Protection Law. This comprehensive regulation is enforced by the Data Protection Authority (DPA) and recognized by the European Commission as an adequate equivalent to other international standards, such as GDPR.

Chile

In addition to being a part of the Budapest Convention, Chile has established a cybersecurity roadmap known as Chile’s National Cybersecurity Policy 2017-2022. The goal of this policy is to implement a strategy that establishes digital security for citizens and businesses alike. It elaborates on the importance of cybersecurity, the potential risks, the necessary procedures, programs, and reforms, as well as the parties responsible for enforcement. It is a beautiful and comprehensive idea. But that’s all it is. An idea that has yet to reach its full potential or see any significant momentum. Aside from Law 19,223/1993 which criminalizes certain computer crimes, Chile has yet to implement any concrete cybersecurity regulations.

On the other hand, the right to the respect and protection of private life and personal data is written into the Chilean Constitution and reinforced by various laws and standards. Law 19,628/1999, or the Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL), includes rules for personal data processing, such as requiring the data subject’s explicit written consent and granting data subjects the right to access, change, and delete data, or revoke consent at any time.

Colombia

Colombia is also a part of the Budapest Convention. What’s more, of the five largest LATAM automotive markets, Colombia has the most comprehensive policies for cybersecurity, cyber defense, and risk management. The National Digital Security Policy (CONPES 3854) establishes a clear framework for cybersecurity mechanisms that focus on strengthening cybersecurity at a personal and national level. The policy lists the designated bodies responsible for regulation enforcement and risk response. Among them are the Joint Cyber Command (Comando Conjunto Cibernético), the Colombian Police Cybercenter (Centro Cibernético Policial), and ColCERT which is the national Computer Emergency Response Team for Colombia.

CONPES 3854 is not the first policy of its time. In 2011, Colombia issued its first strategy on Cybersecurity and Cyber Defense CONPES 3701, which focused on identifying system weaknesses and examining local and international precedents for effective crisis management. The final piece of the puzzle is CONPES 3995 or the National Policy of Digital Security and Trust. Released in 2020, this policy aims to strengthen Colombia’s digital trust and security in anticipation of new technologies and innovations. But don’t get too excited. Despite having a clear and definitive cybersecurity legislature, Colombia still lacks the infrastructure required to implement and enforce these policies to their full potential.

In regards to data protection, Articles 15 and 20 of the Colombian Constitution recognize the right to data privacy and rectification, while additional laws and standards dictate data responsibilities. Law 1581 of 2012 identifies a “data controller” as the person legally responsible for data handling and processing, and the “data processor” is the party in charge of processing on behalf of the controller. From this definition, an entity can be both a controller and a processor. Either way, controllers and processors must implement and maintain strict security measures to prevent the modification, disclosure, or use of data without the subject’s consent. It also prohibits the international transfer of data to any country that does not possess an equal or greater level of data privacy protection, unless authorized by the data subject.

The main body responsible for data privacy enforcement is the Superintendence of Industry and Commerce (SIC). SIC has the power to investigate breaches, place restrictions or blocks on controllers and processors, and issue fines. Penalties for non-compliance can be as high as 528,000 USD and include a suspension of services for up to 6 months. In addition, Colombia’s Criminal Code considers data processing without consent a felony and subject to 4 to 8 years of prison time.

How Do LATAM Regulations Compare?

As we have seen, many of LATAMs cybersecurity procedures and policies are still struggling to get off the ground. However, it is only a matter of time before LATAM countries begin implementing and enforcing more comprehensive regulations. Although no one can predict the exact shape of these laws, it is safe to assume they will resemble other international standards.

It should be noted that most LATAM countries are member bodies of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). In other words, they are working towards universal adoption of cybersecurity standards, such as ISO 21434, and information security management standards, such as ISO 27001. Seeking compliance with ISO and other comparable regulations, like UNECE’s WP.29, will be the best way to prepare for any immediate changes in LATAM markets.

But let’s not neglect data protection. On a reassuring note, most data protection regulations in Central and South America are of the same ilk as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), barring minor country-specific variations. One aspect that OEMs should consider in LATAM markets is data storage. Due to the lack of cyber-secure infrastructure in Central and South America, manufacturers may wish to house sensitive data overseas. OEMs considering this course should pay special attention to the international data transfer laws of their target markets.

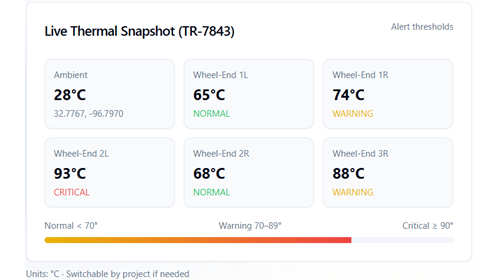

Deploying Sibros in LATAM

For embedded firmware and data management solutions that utilize 5G, WiFi, and Bluetooth for vehicle-to-cloud interfacing, having a compromise-resistant framework is a must. At Sibros, we understand the importance of cybersecurity and data protection, that’s why we place international standard compliance at the top of our priorities list. Our Deep Connected Platform not only enables automotive OEMs with vehicle-wide OTA updates, intelligent edge filtering, remote commands and diagnostics, seamless integration, and complete scalability, but it also complies with relevant safety, cybersecurity, operational, and data protection standards. Ready to deploy your fleet anywhere in the world with confidence? Contact Sibros today.

-min.png)